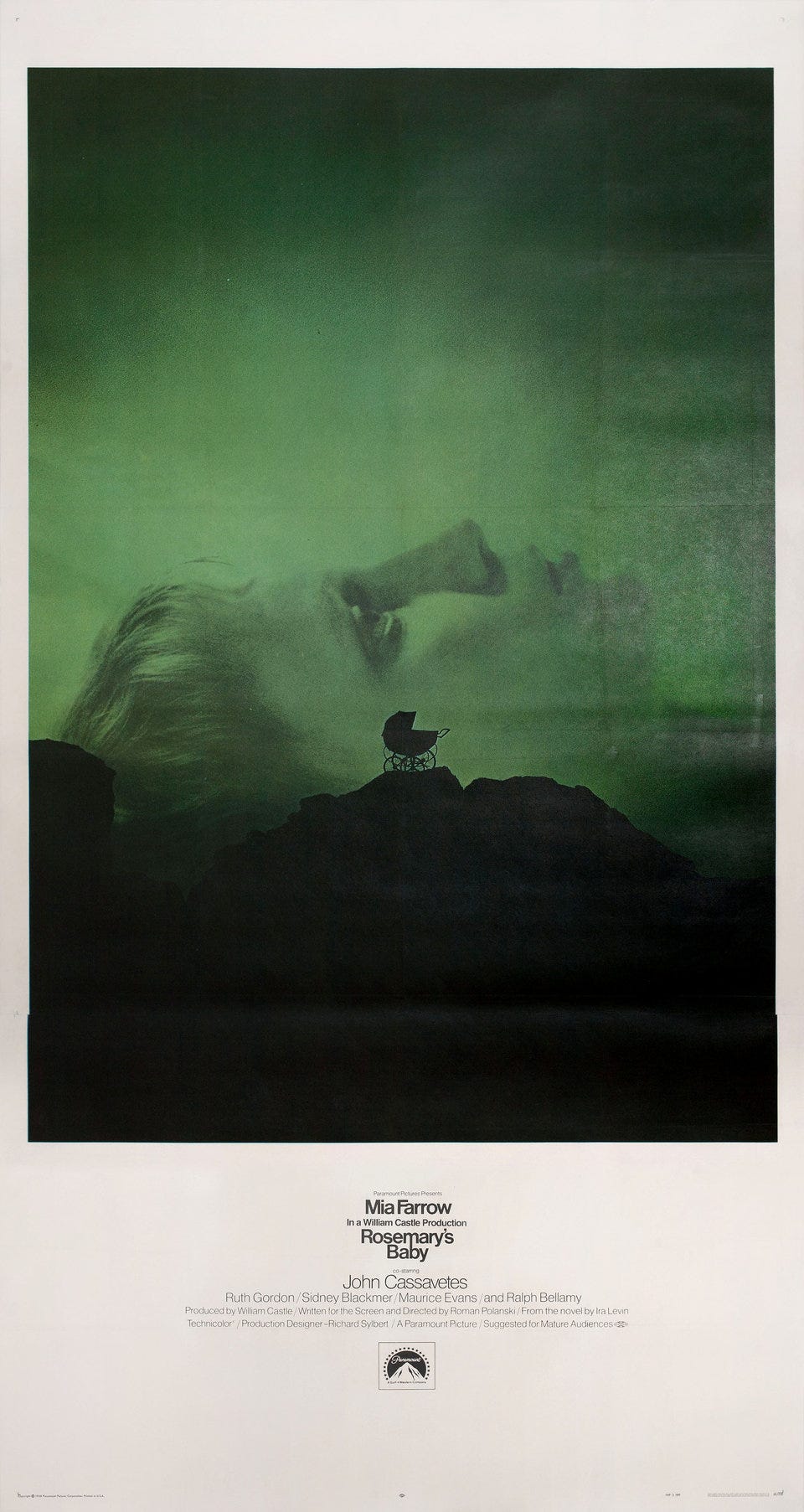

Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

Costumes by: Anthea Sylbert

Directed by: Roman Polanski

This movie may be for you if: you love a 1960’s swing dress, your husband and neighbors may be gaslighting you, you wear a lot of yellow, and you’re constantly fighting the urge to chop off your hair (again).

Where to watch: Included with a few subscriptions (The Criterion Collection, Paramount+, YouTube, Roku Channel, Amazon Prime Video) and available to rent on several other services.

Rosemary’s Baby is a perfect film to me, with the singular exception of the horrendous behavior of its director. Let us turn our attention instead to the three shining stars of this movie: Mia Farrow as Rosemary Woodhouse, Anthea Sylbert as the movie’s costume designer, and Rosemary and Guy’s glorious 60’s Renaissance Revival apartment.

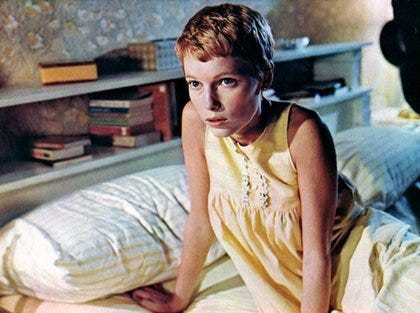

The horror genre often utilizes darkness and gloom, relying on dingy interiors and foggy nights to create a sense of foreboding. Rosemary’s Baby is instead unsettling in its brightness, full of cheerful floral wallpaper, sweet babydoll dresses, and buttery yellow kitchen appliances. The film’s visual levity mirrors the unsteadiness of Rosemary’s world, an eerie reflection of the evil that can lurk beneath picture-perfect aesthetics. The film manages to remain just as scary 57 years later through its masterful use of tension.

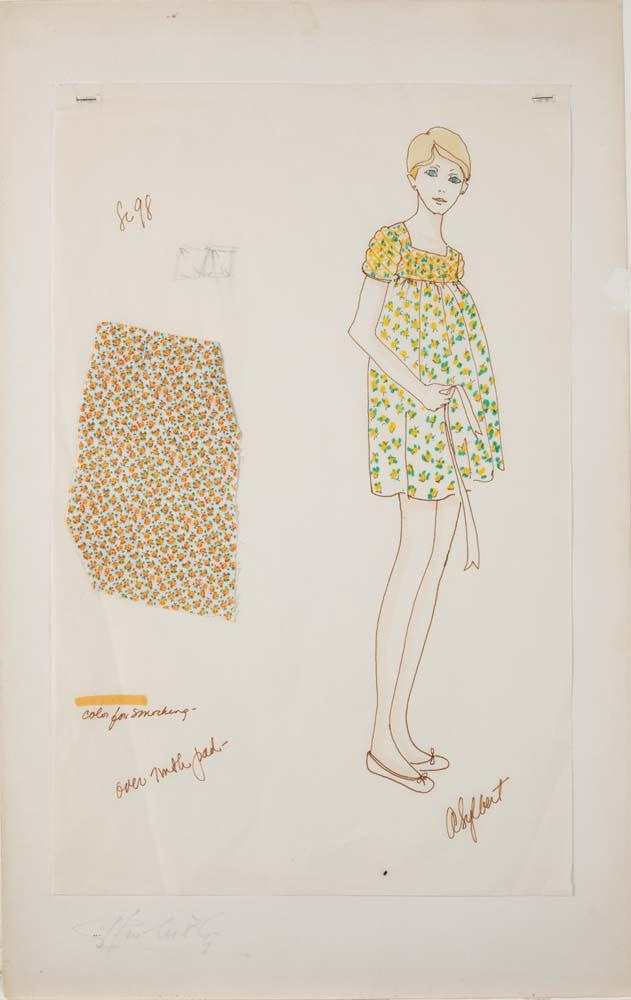

Costume designer Anthea Sylbert dressed Rosemary as the ideal 1960’s gamine - feminine, youthful, sweet. Her outfits feature Peter Pan collars, exuberant prints, and ruffles in swingy, babydoll shapes. Her style was typical of the era, stylish in a way that audiences would find familiar. In Designing Movies: Portrait of a Hollywood Artist, Sylbert recalls her conversations with the director. “'Let's make 'em think we're doing a Doris Day movie,’” Sylbert remembers him telling her. “He wanted everything to look ordinary. People are put at ease by ordinary, and in fact, are put at ease by garish. He didn't want anything in the film to seem sinister."

In contrast to the demure, stylish Rosemary is neighbor and villain Minnie Castevet. Played by Ruth Gordon, Mrs. Castevet wears 1960’s style turned all the way up. Her character is on-trend in a way that viewers are meant to find distasteful - too made up, over accessorized. And worst of all, as a woman: old. Her jewelry is always overized and piled on, even when she’s dropping by in the middle of the day, her blush always harshly applied on her cheeks.

Below is a stunning shot in which Mrs. Castevet makes a phone call from Rosemary’s bedroom, her face and most of the phone obscured from view. (For more on the film’s brilliant camera work, read cinematographer William A. Fraker’s recollections of his experience on set here.)

Color plays an essential role in the film, with entire scenes washed in full monochrome from the furniture to the dresses to Rosemary’s blonde bob. Yellow is a core color, used liberally on both the costumes and the set design as Rosemary and Guy move in and decorate their new home. We first meet Rosemary in a white dress, and we quickly learn she gravitates towards blue, yellow, and neutrals. As the tale progresses, her wardrobe darkens to match her darkening fate, serving as a visual marker of her innocence and purity slowly tarnished.

Vivid splashes of red appear in striking moments throughout the film, jarring in their contrast. Rosemary suddenly appears wearing all red at the start of a pivotal scene in the film, cluing in the audience that something about that night was unlike the others. A single piece of red artwork hangs on their apartment walls, red roses are delivered into a scene otherwise devoid of any other bright colors.

If you’re in the resist-the-urge-to-cut phase of growing out your hair, I do not recommend watching this movie. Rosemary goes from a perfect bob to a perfect pixie, pulling off both cuts with such aplomb that I’m guaranteed to have my hair stylist’s booking calendar open by the time the end credits are rolling.

The film plays with the vital importance of hair and autonomy. As Rosemary’s life and body spiral out of her control, she clings to the choices she is allowed to make for herself. Her dramatic haircut is a final act of desperate self-determination, an attempt at grasping on to her slipping agency, if only in some small part. It also continues a central theme of men’s control over women’s bodies as we see the male characters react negatively to Rosemary’s new hair.

Rosemary: I look awful.

Guy: What are you talking about? You look great! It's that haircut that looks awful. If you want the truth, honey, that's the worst mistake you ever made.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to 1-800-VINTAGE to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.