Colonization Cosplay: The Dark History of an Iconic Mall Brand

Exploitation core and the suburban safari fantasy

What do you think of when you hear the phrase “Banana Republic”? Most likely, you immediately envisioned an inoffensive apparel chain, located somewhere within the pretzel-scented vicinity of a food court. The ubiquitous American retailer has all but reclaimed the term, rendering it essentially meaningless to the modern-day consumer. One of my favorite 90’s button downs is a thrift store Banana Republic find, and I’m always pleased to come across their high-quality vintage knitwear and trench coats. But behind the shiny facade and your aunt’s favorite sweaters, is an unsettling past.

In political science, a banana republic is not a positive term. The phrase describes “a politically and economically unstable country with an economy dependent upon the export of natural resources.” The term was coined by American author O. Henry in 1904 as a way to describe growing foreign economic exploitation by US corporations. Companies like The United Fruit Country, eventually known as Chiquita, was one of several American enterprises deeply invested in destabilizing and exploiting countries like Honduras and Guatemala through plantation agriculture. The crop of choice? Bananas, of course.

Unsurprisingly, the term “banana republic” quickly became associated with racist conceptions of the Central American and Caribbean countries it was used to describe. So where does the clothing store come in? Enter Mel and Patricia Ziegler, the couple that founded Banana Republic in 1978. The reporter and illustrator were often taken to foreign destinations through their work. The duo had a reputation for bringing back interesting garments from abroad, which served as the inspiration for their first store in Mill Valley, California. The new company’s logo was two bright yellow bananas flanking a single star, immediately recognizable on their vintage labels.

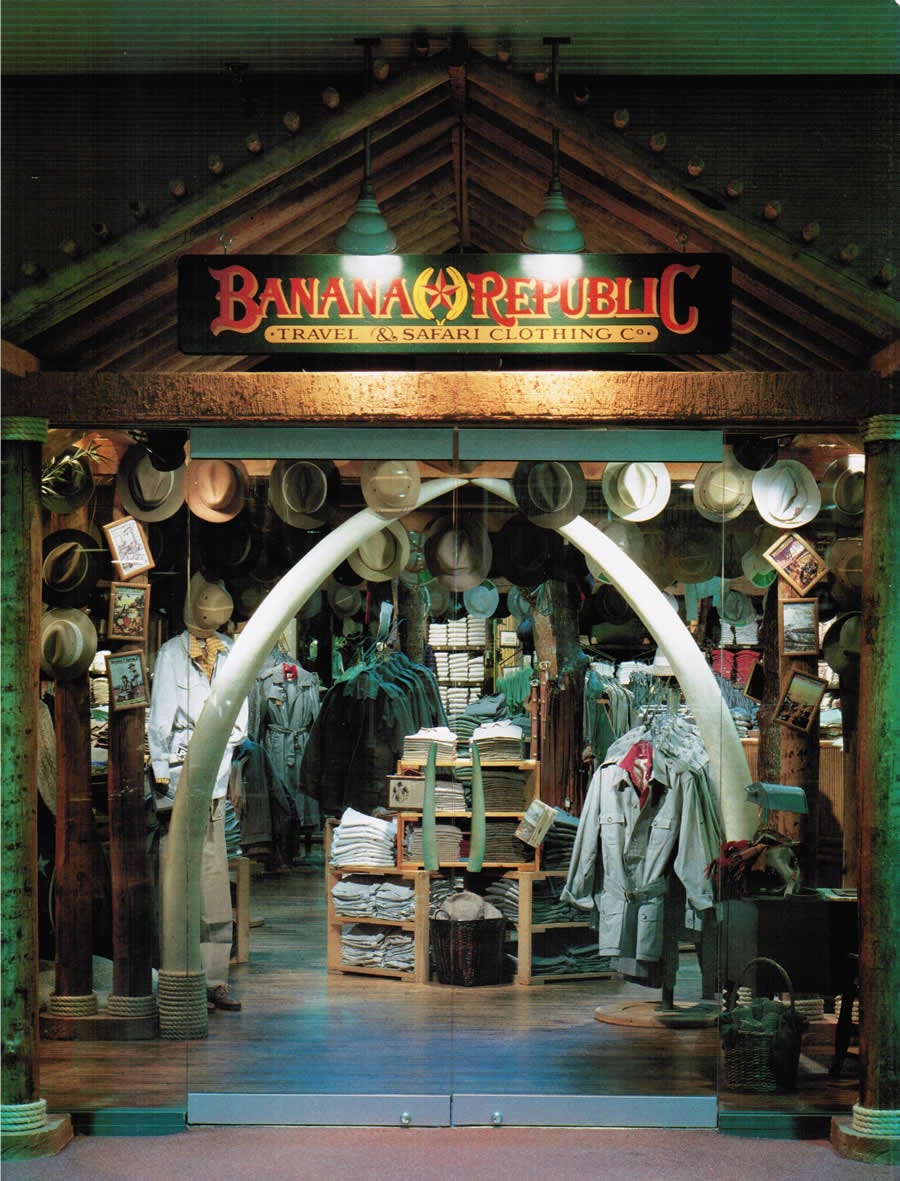

The original Banana Republic was a safari-themed boutique that can best be described as the retail predecessor to Rainforest Cafe. Life-size animal replicas stood amidst living tropical greenery. One location had a Jeep seemingly crashed right through its facade, another had a stream running through the sales floor. The retailer operated with a “Travel and Safari Clothing” tagline, and started off primarily stocking “military surplus sold as a proxy for safari clothing,” as described by Mel in an interview. As the brand grew, they expanded to “finely tailored natural fabric clothing.”

As someone who loves amusement parks and kitschy themed decor, I totally get the people who look back on this era with fondness. But beyond the memorable boutiques and high quality apparel was an unsettling undertone of colonialism and white supremacy. The idea of “safari clothing” is in itself questionable, as the ethics of anything safari-related are. Reverence and emulation of military aesthetics were overt in both the surplus apparel and the overall branding. The Zieglers published a book in 2012, Wild Company: The Untold Story of Banana Republic, with Mel re-iterating the “wildness” of their brand in interviews.

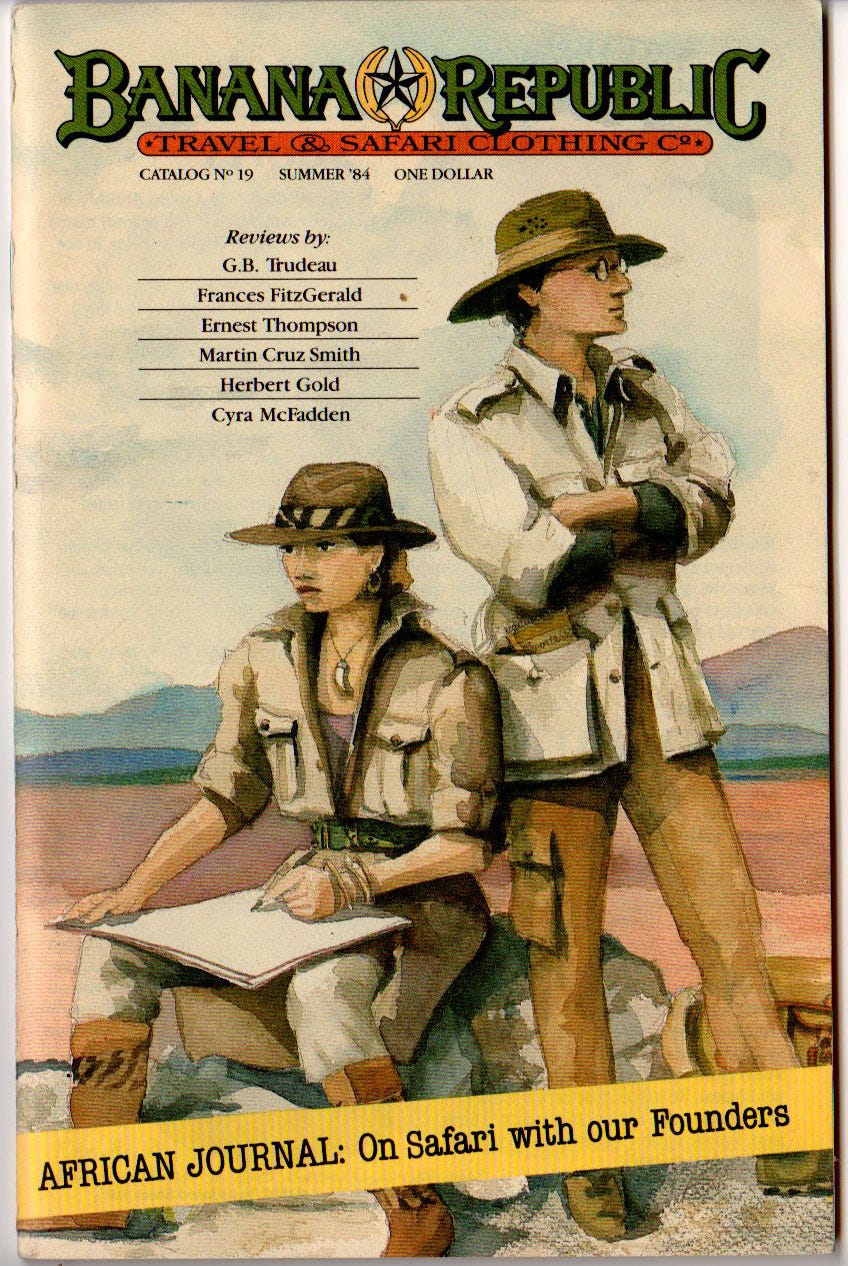

In the Wild Company memoir the Zieglers discuss their first safari trip to Africa in 1984 and marvel at the “Cheaply made, misshapen, ill-conceived, impractical, shiny polyester safari clothes….Only ersatz safari garb can be found in Nairobi. We in California are the default source for the best selection of the real thing.” (Via Abandoned Republic)

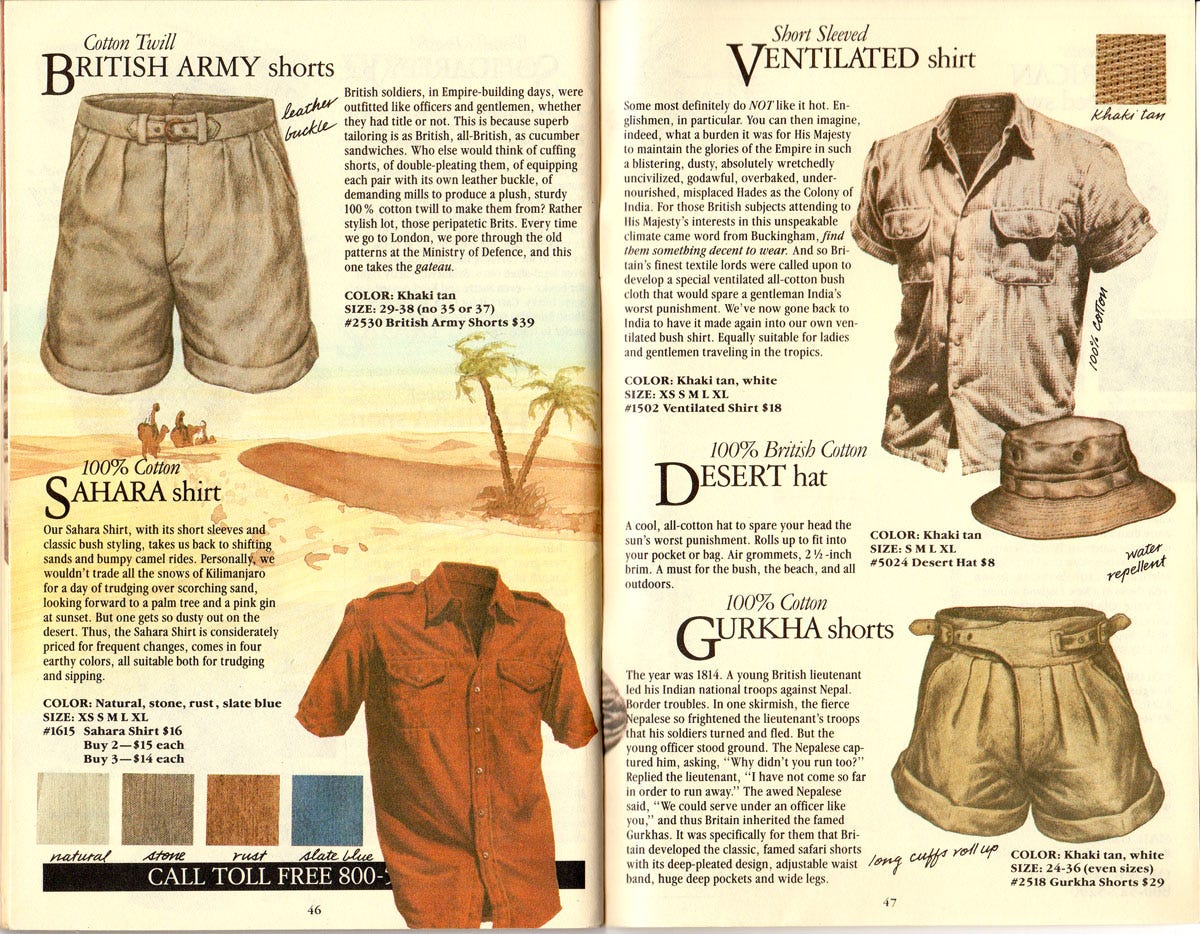

The lushly illustrated catalogs are devoid of depictions of the actual people or laborers from the “exotic” countries in question, focusing instead on ghostly clothing floating without bodies beneath. The product copy is often written from the point of view of “us” and “we,” seemingly in reference to the Zieglers themselves, detailing memories and experiences from the perspective of an outsider.

The spectacular foreign goods for sale are described in secondhand retellings, with mention of artisans and craftspeople that never seem to have names or faces or any kind of real credit. The emphasis often falls on the “discovery” of such items, as though the American explorers coming across such pieces are the real heroes. Few stories are told about how or why certain styles came to be, instead focusing on the moment at which the Zieglers, or another similar white adventurer, first came across them. While some of the pieces shown do come with seemingly accurate cultural background, others offer perplexing descriptions. One catalog page points to Tanzania’s Serengeti Plain as inspiration, with copy for the “Serengeti Skirt” starting as follows: “Like the fine gentlewomen of the British Empire, who dressed in similar garments, the Serengeti Skirt is stylish yet very nearly indestructible.”

“Some most definitely do NOT like it hot. Englishmen, in particular. You can then imagine, indeed, what a burden it was for His Majesty to maintain the glories of the Empire in such a blistering, dusty, absolutely wretchedly uncivilized, godawful, overbaked, under-nourished, misplaced Hades as the Colony of India. For those British subjects attending to His Majesty's interests in this unspeakable climate came word from Buckingham, find them something decent to wear.”

Copy for the Short Sleeved Ventilated Shirt

The above example was one of the worst I found. But aside from the occasional bout of straight up racism, much of Banana Republic’s aesthetic leaned on murkier ideas. And of course, it’s easy to judge the morality of 70’s and 80’s copywriting with a modern eye. The brand’s “global” perspective was probably seen as pretty progressive for the time, and I can find little discussion about the problematic sentiments that lurk behind the wilderness fantasy.

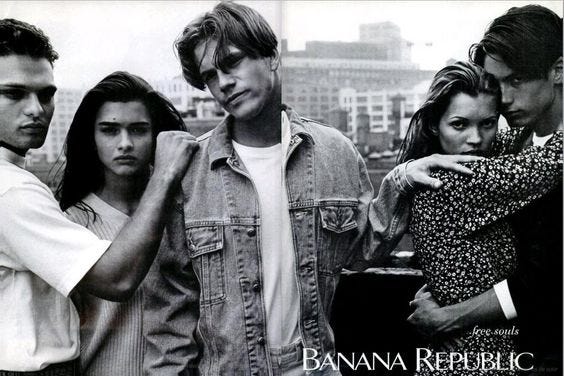

The Zeiglers themselves only retained ownership of Banana Republic for five years. The brand was such a fast success that it was bought by Gap in 1983, with the founding couple pushed out of their creative direction roles by 1988. The company pivoted from the earlier themes into a more widely palatable direction, positioning the quickly growing brand as a top seller in the American masstige market.

So what did the Zieglers do with their time once their safari apparel chapter came to an end? Start another company, of course. The duo partnered with Bill Rosenzweig to start The Republic of Tea in 1992, once again leading with the “republic” concept.

Similar to their apparel venture, the Zieglers used The Republic of Tea to introduce global products to the American consumer. The brand was also sold after just a couple of years, and exists today as a successful but seemingly modest business, focusing on sustainability and fair-trade farming. Here’s the weird part: according to their website, the brand refers to its employees as “ministers,” sales reps as “ambassadors,” customers as “citizens,” and its retail outlets as “embassies.” While the brand itself seems fine, if not actually operated pretty ethically, the fixation on global political dynamics is strange to say the least. The “About Us” page of their website reads enthusiastic but honestly, a bit-cult like.

Today, Banana Republic carries few signs of their Safari-themed past. The sleek storefronts and stylish ecomm presence appear a better fit for the cubicle than the jungle. However, the company launched a rebrand in 2021 with marketing that nodded at the retailer’s heritage themes. The resulting campaign, titled “Imagined Worlds,” marked a return to the globe-trotting obsessions of the brand’s past. So what does all of this mean?

This letter is neither forgiveness nor endorsement for Banana Republic as a company. Their vintage apparel is generally of very high quality, and their current offerings seem to be an okay option in an increasingly bleak fashion landscape. However, I think it’s of vital importance to understand how easy it is for genuinely disturbing ideals to become the romanized aesthetic of seemingly commonplace objects. The America we’re currently grappling with, on the heels of a frightening election, is simply a bold projection of what has always lurked behind our unique brand of capitalism and individualism. Our country’s picket-fence fantasy embraces outside (ie non-white) culture only from the lens of adventure, exploration, and reclamation. The garments and styles of far-off artisans become acceptable only once they’re being peddled by the brave white people who went to go get them for you.

And while one single store in the mall certainly isn’t to blame, Banana Republic does feel like a particularly stark example of how deeply colonialism, militarism, and imperialism are embedded into everything from our TV shows to our sweaters.

One particularly popular item was the “Authentic Israeli Paratrooper briefcase.” Dozens of online commenters share fond memories of carrying this exact bag from Banana Republic, mostly as young students. The catalog images make no mention of what “Made in Israel” meant for the besieged citizens of Palestine, or what the implications of owning IDF tactical gear would signify for the young Americans carrying the bag. As I wrote about in an earlier essay, there is truly no such thing as “just clothes” or “just fashion.” Every item selected in our wardrobes, regardless of our process, has deeper implications about the world around us.

So for now, I’ll continue wearing my favorite vintage Banana Republic button down. It’s a nice shirt, 100% cotton, and I thrifted it for under $10. But I do hesitate every time I glance at the tag in my closet. Maybe someday I’ll decide to swear off the brand entirely, but for now, I’m just thinking…

Sources:

Most of the store photos and catalog images come from the very thorough archive of Abandoned Republic: A Journey Through the Vintage Banana Republic Catalog

7 Facts About Banana Republics & Their Role in History and Politics

The True Story Behind the Banana Republic Brand

On Safari to find Banana Republic