Did Cinderella Kill Schiaparelli?

The Disney-fication of Dior and the fall of Maison Schiaparelli

A quick note from me:

I messed up when first publishing this piece. This essay was inspired by a theory presented by art historian Emanuele Lugli, who I reference and quote throughout. I was so taken by the many convincing parallels in his writing that I was admittedly a bit swept up by the whole idea. This theory is indeed just that, a theory, and I should have done a better job of presenting it as such. I find Lugli’s references and comparisons very compelling, and strongly believe in the credence of these ideas in accordance with the timelines and examples presented. However, no statements by animators were ever provided as direct confirmation.

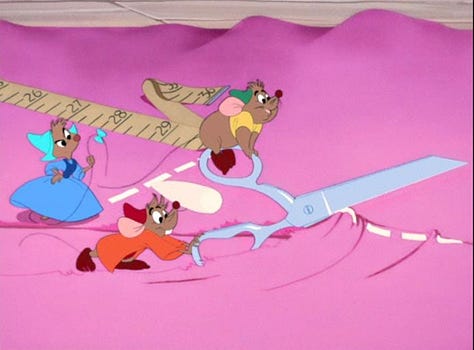

We all know the story: she scrubs, she sings, she’s swept away in a pumpkin before losing her shoe and living happily ever after. Cinderella is the ultimate fashion fantasy, if your fantasy involves mice with scissors and marrying a man you literally met once. Okay, all jokes aside, I get it. The perfect dress is materialized out of thin air, your shoes are so custom that they won’t fit anyone else in the entire kingdom. But why did Disney decide to make the “perfect dress” a shimmering, voluminous gown? Why was her first dress, before being torn to shreds, bright pink and covered in bows?

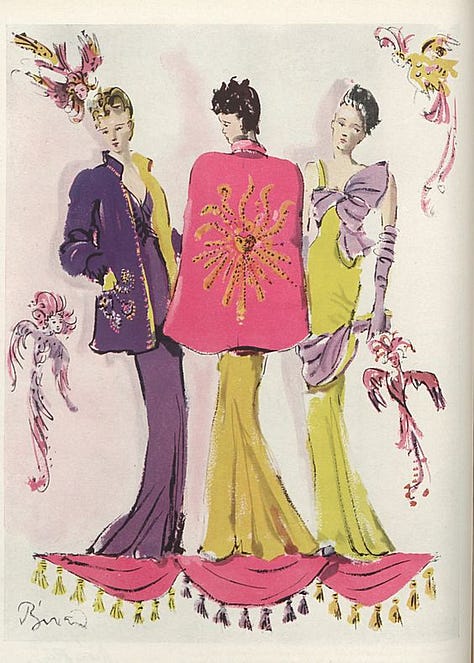

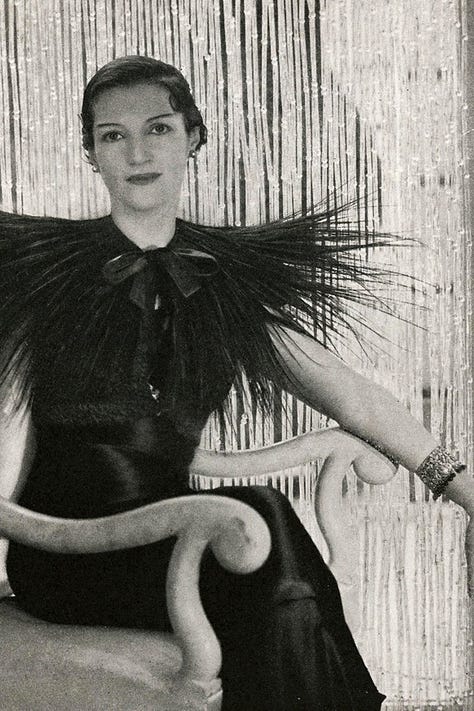

Unbeknownst to many today, Disney’s Cinderella was actually a statement about the changing Western fashion industry following WWII. Cinderella’s first dress was a remake of her mother’s “old fashioned” dress, likely from the 1930’s. And it was no accident that the upcycled look was vivid pink with big bows - both were signatures of Elsa Schiaparelli, and Disney was purposely being shady. Schiaparelli was well known for adorning her designs in bows, often sporting them herself, and here was Disney saying that the bows were literally for the birds.

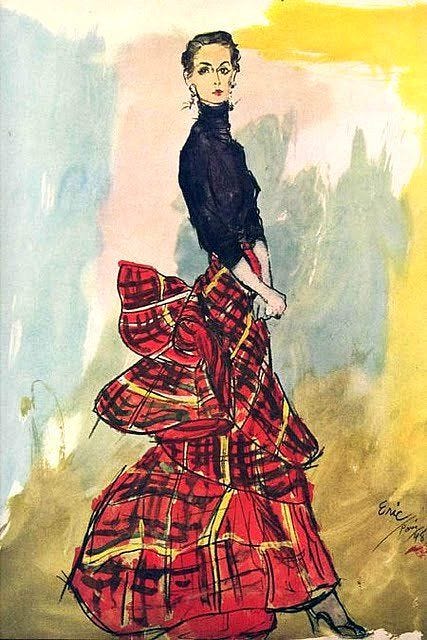

The stepsisters also wore unsubtly Schiaparelli-inspired looks in (what are clearly supposed to be perceived by the audience as) garish colors. Art historian Emanuele Lugli writes in his fascinating analysis: “Her stepmother and sister destroy [her dress] because they, too, are wearing Schiaparelli (who in 1948 revived dresses with end-de-siècle panniers on the back, an homage to Toulouse-Lautrec). Cinderella’s humiliation - the step-relatives literally leave her in rags - may represent a narrative zenith, but fashion wise it simply reinstates Cinderella’s outdated taste.”

Even the torn-up dress Cinderella ends up in is thought to be a direct reference to Schiaparelli’s 1938 tear dress, created in collaboration with Salvador Dalí. Cinderella’s personal taste was as outdated as her terrible siblings’, never mind the design choices of literal vermin. A magical being from the new fashion elite, otherworldly but caring, was the only one who could swoop in and save Cinderella from her unfortunate inclination towards the so tragically 1940’s Schiaparelli.

The implications are pretty clear: Cinderella looked okay, and her upcycled mouse-dress was fine, but she deserved something even better than the same designer her awful sisters were wearing. And that better thing was a shimmering, demure, New Look-inspired gown pulled straight from the house of emerging designer Christian Dior. This film was a clear commentary on Disney’s opinion of post-war fashion in America, offering the fairy tale dream through subservience, song, and a little bit of designer magic.

The stepsisters are villains, and it’s portrayed as a character flaw that they have so much more autonomy and opinion in their clothing choices. They tear through their wardrobes, flinging the not-right pieces across the room, more relatable to most of us than Cinderella’s swanlike scrubbing. Their frantic dressing is portrayed as cringe-worthy vanity that does nothing to disguise their inner ugliness. Meanwhile Cinderella’s outfits are decided almost entirely by others - though this isn’t by choice, the idea that she’s dressed up like a doll is clearly the morally superior position. Lambasting feminine interests is by no means anything new, and the story serves as yet another example of vain, fashion-obsessed women (in Schiaparelli) pitted against the pure, mannequin-like character of Cinderella (in Dior).

Lugli again: “And while it is true that her stepsisters are ridiculed for wasting time on idle accessorizing, Cinderella is never chastised for wearing a ball gown… But then she is spared any criticism because she is a hard-working, obedient woman - a reasoning that Max Weber first found in Calvinist preaching and considers the foundational tenet of capitalism. Indeed, by showing how submissiveness and productivity justify consumption and lead to salvation, Cinderella is the quintessential capitalist fable.”

Another layer is revealed in the process by which each look is made. Cinderella’s mother’s original dress appears to represent the home sewists of the past, while the scurrying teamwork of the singing woodland critters was a thinly veiled reference to the manual labor of traditional couture houses. The post-war era marked a shift from made-to-measure to ready-to-wear, with rising designers like Dior distancing themselves from the “old fashioned” processes. Though Dior was very proud of the meticulous handiwork behind his creations, he separated himself from the material labor of his designs. Dior was not a mouse or a bird but the fantastical Godmother, bestowing the worthy with the life-changing magic of the right outfit.

Writes Lugli, “Chanel ‘prided herself on being unable to sew a stitch,” writes Dior, who followed her lead and detached himself from manual labor. He is hardly photographed while holding a pin. Instead he sketches on boards, contemplates fabric swatches, or points at features of dresses with his signature cane. But this is exactly what Cinderella’s godmother does.”

The critters and their scissors were replaced by a magic wand and swirling glitter, swiftly and effortlessly creating a look that saves Cinderella from a life of unjust servitude.

This is all fascinating to look back on from 2024, when we perceive Disney and Dior as titans of their industries. In the late 1940’s, when Disney was in the midst of creating Cinderella, this wasn’t the case for either. The movie studio was on the brink of bankruptcy, suffering major losses from being cut off from the European market during the war. Their prior releases, Pinocchio (1940) and Bambi (1942), were commercial failures, and they were in serious debt. Cinderella was a success both critically and commercially, essentially saving Disney from an impending closure and making the princess a core component of the brand’s identity.

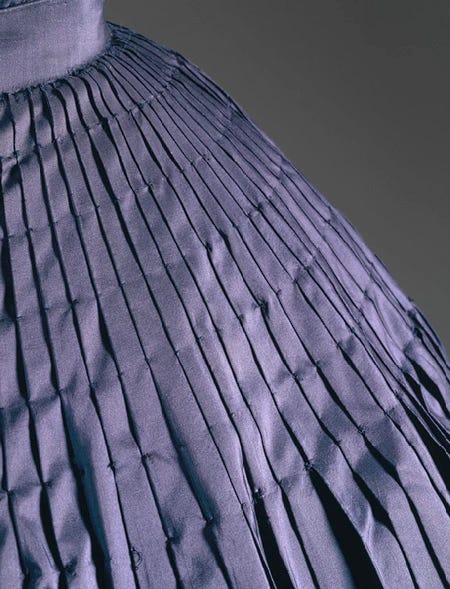

Meanwhile, emerging French designer Christian Dior was receiving about as much criticism as he was praise. While some saw his designs as a much-needed return to pre-war extravagance and femininity, others perceived his voluminous creations as wasteful. Dior’s Chérie, for Spring/Summer 1947, utilized an entire width of fabric for the skirt, selvage to selvage. The public had grown accustomed to fabric rationing, and the sudden appearance of full, floor-length gowns during post-war recovery was so shocking that it was even considered by some to be unpatriotic.

Beyond accusations of wastefulness, others felt like Dior’s New Look was an attempt at returning women to restrictive, matronly styles that many were eager to leave behind. American protestors picketed his shows with signs that included slogans like “Mr. Dior, we abhor dresses to the floor” and even Coco Chanel chimed in with her two cents, “Dior doesn’t dress women. He upholsters them!”

As the west continued to recover from the war both economically and culturally, there was a marked shift in the public perception of Dior’s designs. The New Look became very popular as consumers eagerly embraced life after the darkness and austerity of war, and the success of Cinderella likely had a hand in Dior’s success. So, does that mean Cinderella also had a hand in Schiaparelli’s demise?

Sadly, Dior’s rising star seemed to rely on the momentum of Schiaparelli’s falling one. Maison Schiaparelli saw such a decline during the postwar era that the house declared bankruptcy in 1954, only a few years after Cinderella first appeared in her shimmering New Look gown. While the closure of a once-successful fashion house could never really be pinned down to a single dress, I can’t help but wonder if Cinderella played an outsized role in Schiaparelli’s fall. The animated film received three Academy Award nominations, and the story’s clear moralizing around fashion had to have some kind of impact on its very large audience.

Schiaparelli was revived in the 2010’s with a 2014 collection by Marco Zanini and the re-establishment of their Parisian boutique. The house has experienced a mainstream renaissance in more recent years, particularly since the appointment of creative director Daniel Roseberry in 2019. The house was accepted into the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture in 2017, making it one of only 15 fashion houses legally allowed to use the designation of “Haute Couture.”

Today, Schiaparelli and Dior continue their legacies as brands with directly opposing images. In contemporary internet culture, I’d argue that Schiaparelli is more “fashion girlie” and Dior is more “trad wife.” The New Look was influential in shaping the traditionally feminine silhouettes of the 1950’s, a decade remembered for its particularly “all-American” aesthetic. For many, the 1950’s conjures images of a white-picket-fence suburban life that aligns with the “Great Again” America that conservatives so desperately want to go back to. Dior as a brand is familiar, safe, and palatable, just like Cinderella.

In contrast, Schiaparelli has always had a reputation for avante-garde design, including Elsa’s frequent collaborations with surrealist artists like Man Ray and Jean Cocteau. The brand is known for its signature shocking Schiaparelli pink, sculptural design elements, and illusion designs like trompe l’oeil. It’s actually easy to imagine the loud, flashy stepsisters finding charm and humor in a lobster dress or earrings shaped like golden ears. The male animators behind Cinderella’s world created villains that embraced characteristics they themselves would find unappealing in a woman: loud and opinionated, shrieking and giggling, all while wearing bold looks and bright colors.

There’s been a growing online conversation around the over-intellectualization of fashion and style. Everyone is a trend forecaster, everyone is a stylist, everyone has a formula or a checklist for shopping and dressing and emulating and critiquing. I have to agree with the sentiment as a whole, even as someone who’s attempting to carve out her own online space to join in on the fashion-spewing. Maybe especially so. And how fascinating that despite discourse on qualifications and credentials, some of the most common-denominator media is entrenched in relatively unknown fashion history. Are we so obsessed with seeking out the obscure, in identifying the “new,” that we’re too quick to overlook what we already think we’re familiar with? Knowing this version of the Cinderella story probably won’t affect most people in their day to day. But now I’m wondering what hidden histories are lurking behind the seemingly most basic, most well-known stories. Don’t worry - when I find them, I’ll be sure to rant endlessly to you about that, too.

This rabbit hole of a piece started with research for a personal endeavor I’ve been working on, The 100 Fashion Films Project. I’ve been making my way through a carefully crafted list of 100 movies that have strongly impacted western fashion and style. Each movie gets a review video on TikTok, and each video requires me to essentially write a full length essay as preparation. While I knew that Cinderella was iconic in terms of “the look” - I mean, just the shoes! - I was really surprised by the layers of fashion commentary that seem lost on most viewers, including myself. I had no idea that all of this historical fashion context existed behind an animated movie I’ve seen dozens of times, and inevitably fell into a serious rabbit hole. Turns out, Cinderella very may well be the most Fashion Film-y Fashion Film of all. It’s only movie #40 on the list so far, so we can revisit that distinction once I’ve finally made my way through. If you’re interested in seeing my video review of Cinderella or any of the 39 other movies I’ve covered so far, follow me on TikTok at @st_evens.

Sources and Further Reading:

Tear That Dress Off: Cinderella (1950) and Disney’s Critique of Postwar Fashion

What Not to Wear: Clothing Rationing During WWII

Everything You Need to Know About Christian Dior’s New Look Silhouette

This Day in History: Christian Dior launches his scandalizing “New Look” postwar fashions

The History and Evolution of Christian Dior’s New Look

Maison Schiaparelli - Elsa Schiaparelli & The Artists, Salvador Dali